Core to Margherita Moscardini’s artistic research is the critique of the urban processes typical of the contemporary neoliberal city. The public space — the street, in the broadest sense — can be seen as the most striking product of global economic and social processes that tend to harden its discipline and its regulation through the marginalisation of the most vulnerable. Faced with this reality, the artist looks to manifestations of urban conflict as she seeks new possible representations and ways of escaping the tightly woven securitarian conception of urban space. Moscardini’s research always starts from an observation of reality — of social and anthropological, architectural and urban factors. She often ventures to take paradigmatic portions of the social and urban fabric and transform them into sculptures or drawings. In this sense, her works pose deep questions about the meaning of public space; about the relationship between subjectivities and architectures, between built spaces and the formal and informal ways of inhabiting them; and about how humans could, potentially, rewrite cities.

The erosion of the public dimension of squares and streets prompts the artist’s reflection on the practices of contestation and conflict, as constitutive agents of public space. As Judith Butler states, when “bodies in their plurality lay claim to the public, [they] find and produce the public through seizing and reconfiguring the matter of material environments; at the same time, those material environments are part of the action, and they themselves act when they become the support for action.”[1][DB1]

One example of this is Istanbul City Hills. On the Natural History of Dispersion and States of Aggregation (2013). Here, the artist’s research starts precisely from the observation of urban transformations, and from the neighbourhoods demolished for the sake of real estate speculation and gentrification. The debris is itself used by the artist as a metaphor for these transformations, which reconfigure a landscape created through dispersions and new aggregations. This allows an interpretation of the turmoil and the dynamics that deconstruct and reconstruct urban geographies, which here take on plastic dimensions,[2] as the artist herself states: “the crowd is an organism that moulds itself on the built: it becomes the positive of the negative constituted by the urban voids; and whether the individual isolates herself or holds on to the body of the organism, it does not change her substance as a dispositif, which by occupying the void continuously measures, shows and reconfigures architecture. She herself becomes architecture”.[3]

It was while the artist was working in Istanbul, where she had the opportunity to observe the street protests and the Gezi Park revolution at close quarters, that she developed the conviction that her work should be a mechanism for interacting with reality.

The theme of the right to the city, to inhabit it, is the constant tension that moves the artist in much of her research and production, transforming her sculptures into spaces, into places with an extraterritorial status, in open contradiction with international norms on the right to asylum and, more generally, with the modern conception of nation-states. On the other hand, “The city is the people, as Hannah Arendt argues, and people move, cities move and challenge the obsolete boundaries imposed by geopolitical maps, and it is also up to artists to create critical mechanisms, tampering with the present and breaking through a paradoxical reality where people’s right to move, to migrate and not to belong to any nation is violated”.[4]

Starting from the observation of one of the Middle East’s largest refugee camps — the Za’atari camp in Jordan — and studying the physiognomy of its settlements, Moscardini recognised the courtyard-with-fountain as a typical feature of the spontaneous architecture which inhabitants design in compliance with their needs and requirements. This self-constructed space has been mapped and redrawn by the artist in its various configurations, eventually producing a catalogue of models, which have so far taken the form of drawings or scale sculptures. The catalogue is conceived as a commercial device: the European public body wishing to reconstruct one of the fountain courtyard models on a 1:1 scale pays royalties to the Syrian designer who built the original fountain in Za’atari. But the central point of this comprehensive, long-term project is the processoftransforming these sculptures into extraterritorial spaces.

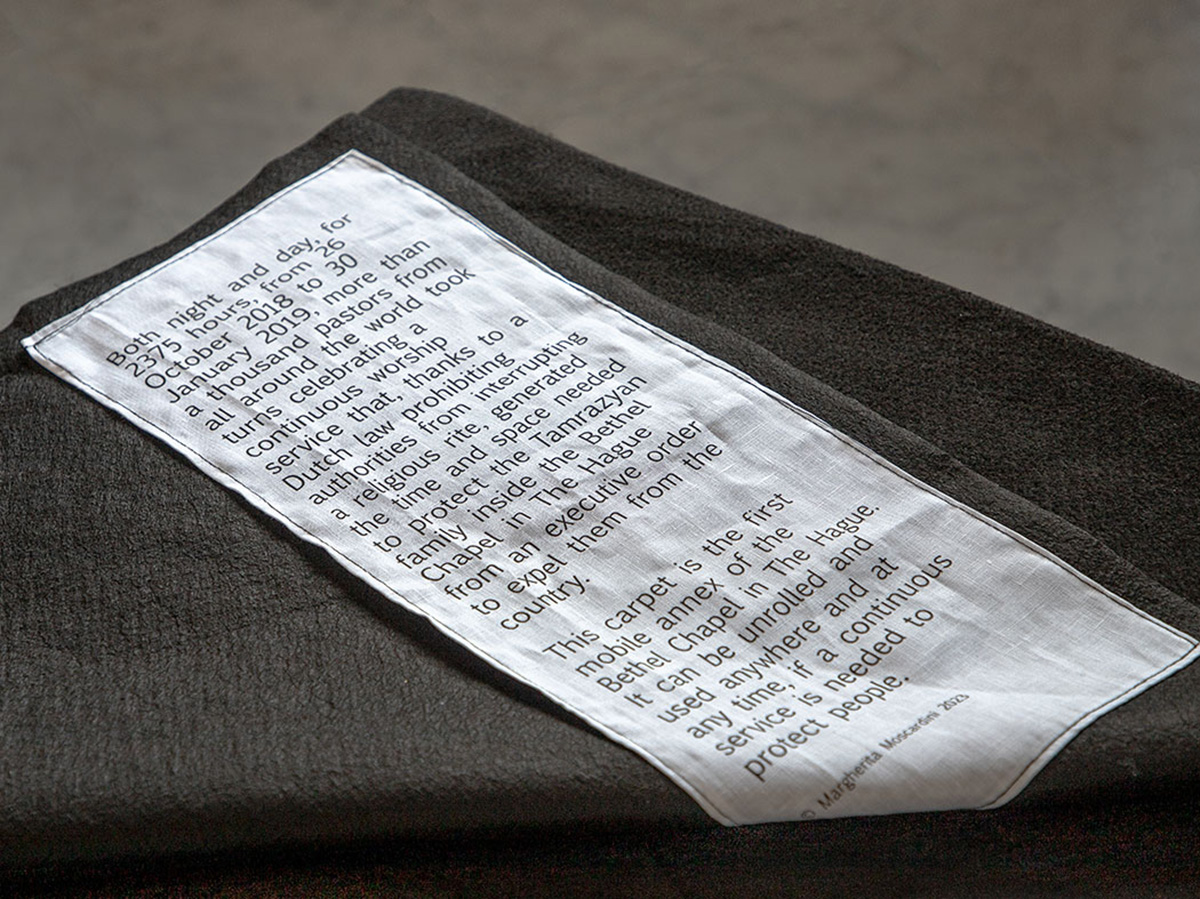

Moscardini imagines sculpture as the creation of a space of immunity, through the definition of formal acts that free the works from territorial sovereignty. This means, both as an ideal and in fact, restoring the possibility for art to become a free, safe space. Inspired by the Roman principle of res communes omnium, the artist recreates the conditions for her works to be like the free zones of the high seas, states of utopia, which can be inhabited as “resident foreigners”.[5] A further example of this comes in one of her more recent works, Bethel Chapel’s Annex (2023). Here, the artist connects with the exceptional story of the uninterrupted Mass held for around three months by over a thousand ministers of the Bethel Chapel church in The Hague, in order to protect the Armenian Tamrazyan family from the executive order expelling them from the country. The artist creates an additional space, legally and ideally annexed to the Bethel Chapel in the form of a five-hundred-square-metre carpet, a mobile and itinerant space formally bound to the chapel. It can be used again, anywhere, and represent a safe space, which questions the humanity of laws and widens its meshes through an act of disobedience, reinventing the possibility of a non-normal place and time.

So, the work on public space that we find in Margherita Moscardini’s oeuvre is configured rather differently from that research in these last twenty years that has expressed itself directly and physically in squares or streets. Her practice is driven by a tension, also common to other artists of her generation, that looks to the urban field as a research-setting in which a utopian or at least a liberated dimension can be reconfigured. It is a dimension in which the urban is reconstituted in an “elsewhere”, becomes the material and metaphor of a radical perspective, of a refoundation of what exists.

[1] J. Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, Harvard University Press, 2015, p. 71.

[2] As part of the same project, the artist also produced several ink drawings.

[3] D. Bigi, “Margherita Moscardini. Istanbul City Hills,” in Arte e Critica, LXXV-LXXVI, 2013, pp. 118-119.

[4] M. Trulli, Studio visit a Margherita Moscardini, <https://quadriennalediroma.org/margherita-moscardini/> (July 5, 2023).

[5] In this regard, Moscardini often cites essays by Donatella Di Cesare, such as: Stranieri residenti, Bollati Boringhieri, 2017 [Resident Foreigners: A Philosophy of Migration, Polity, 2020].